Palace Culinary CultureIn fact, even without looking at the previous periods, only the 19th century is a period in which changes were experienced for the elite Ottoman cuisine. The materials used in the kitchen differ throughout the century, at the end of the century it is seen that..

Istanbul and Ottoman Palace Culinary Culture in the Last Period of the Empire

*Ozge Samanci

The elite Ottoman cuisine, which was formed and developed by kneading with different cultural elements in a long historical process, appears with a multi-layered and rich table in the last period of the empire. In the 19th century, the Ottoman palace cuisine culture or the Istanbul cuisine culture both have many common aspects and show differences with the classical period Ottoman cuisine.

Palace Culinary CultureIn fact, even without looking at the previous periods, only the 19th century is a period in which changes were experienced for the elite Ottoman cuisine. The materials used in the kitchen differ throughout the century, at the end of the century it is seen that new techniques are started to be applied in the kitchen, table manners and order begin to change.

There are more than one reason for all these changes: The first is that foods of American origin such as tomatoes and beans, which started to enter the Istanbul cuisine since the end of the 18th century, are now being recognized and adapted to the palate. Another is Istanbul's increasing commercial and economic ties with Europe, especially in the second half of the century, which has diversified the quality of food supplies to the city. Another and the most important driving force of the change is that some European cultural patterns started to be gradually recognized and accepted in Ottoman elite circles since the Tanzimat period.

In this article, the food culture that was formed in and around the Ottoman palace and palace in the 19th century will be discussed under the headings of the structure and personnel of the kitchens, foodstuffs and types of dishes. While presenting information within the framework of the aforementioned topics, the questions of how the 19th century Ottoman cuisine was compared to the previous centuries and whether it was differentiated during the period studied will be answered. In the study, the Ottoman Palace cuisine is mainly discussed, but at the same time, the culinary culture that was formed in Istanbul in the 19th century is also tried to be clarified. The sources used in this article mainly consist of accounting books belonging to Ottoman palace kitchens and Turkish cookbooks with Arabic letters published in Istanbul in the 19th century.

Kitchens and Cooks

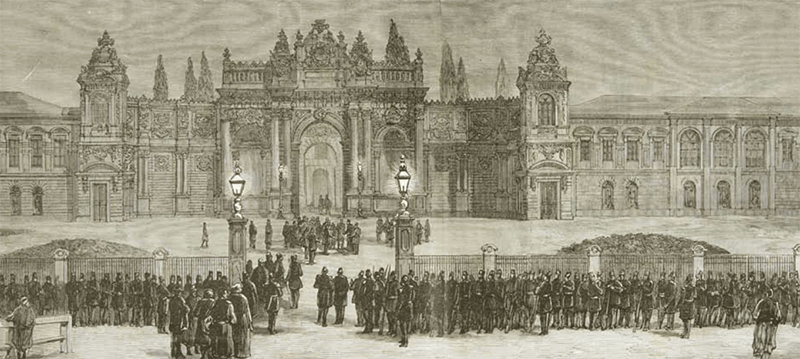

Ottoman palace kitchens are distinguished from mansion kitchens and ordinary household kitchens in Istanbul with both their spatial organization and detailed personnel organization structure. We can compare the palace kitchens to giant food factories that provide food to more than a thousand people every day. The kitchens of Beşiktaş Beach Palace (or Old Çırağan Palace), which hosted the Ottoman dynasty in the 19th century, and Dolmabahçe Palace and Yıldız Palace, which were built instead of Beşiktaş Palace, are similar to the kitchen structure in Topkapı Palace.

Sultan II. In Beşiktaş or Çırağan Palace, where Mahmut lived from 1809 to 1839 and Sultan Abdülmecit until 1853, the kitchens consisted of several sections. Apart from the general kitchens, the meals prepared for the sultan were prepared in a separate unit in the kitchen called Kuşhane-yi Hümayun or Matbah-ı Has, while the kitchens serving the harem and the palace band (muzıka-yı Hümayuna) were also separate. There was also a bakery, a halvah restaurant and cellars in the palace. At the same time, the palace kitchens were also divided into units called quarries, and each quarry served a different unit: such as the prince's quarry, the treasurer ağa quarry, the kethüda women's quarry, the masters' quarry, the expeditionary kethüdasi quarry, and the cellar-ı Enderun-ı Hümayun Ağavatı quarry.

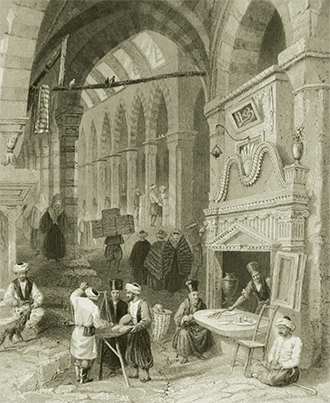

The kitchens in the Dolmabahçe Palace, the construction of which was completed in 1856, also consisted of several sections. The kitchens (matbah-ı amire), which served the harem and the officials in the palace, were located in the last structure of the palace, towards Beşiktaş, which was connected to the harem section by the Aş Gate. In this structure, which is a classical functional complex with a courtyard, meals were served to the people of the palace and the meals were brought to the apartments by the aghas. Dolmabahçe Palace kitchens, with domed and arched hearth sections around a courtyard, were similar to the Topkapı Palace kitchens in small dimensions.

There were production structures connected to the kitchens on the side of the Bayildim Garden, which constitutes the first parts of the palace. Kuşhane-yi Hümayun, the kitchens of the princes, ovens, cellars, a mill and a dessert house were located here. In addition, two separate kitchens that served the sultan and the valide sultan in the palace, independent of the matbah-i amir, were located within the body of Harem and Selamlık under the name of Has Kitchen.

Sultan II. In the Yıldız Palace, which was used as a palace-ı Hümayun during the reign of Abdülhamit (1876-1908), the kitchens were located behind the mabeyn-i Hümayun and harem buildings, between the warehouse and the armory. In addition, there were chickens, pigeons, vineyards, orchards, conservatories and a yoghurt house serving the kitchens within the palace. Hundreds of dishes were cooked every day in Yıldız Palace, where it is said that 12 thousand people lived.

Apart from the Sultan's kitchen (matbah-ı hassü'l-hass) and the harem kitchen, the kitchens in general, according to the people they served, were the princes' kitchen, the gunsmith's stove, the Daghestan hearth, the hearth allocated to the harem of Sultan Abdulaziz (the deceased harem-i humayun hearth). ), the muzika-yi humayun kitchen, the boatmen's kitchen, and the palace stables kitchen.

In addition, the kitchens were divided into specialties such as the big hearth, the new order hearth (tertib-i cedid hearth), the pastry oven, the dessert oven, and the diet oven. There were many servants working under these kitchens.

For example, according to a salary book of 1882, the number of employees working in the kitchens of Yıldız Palace was 907. These included those responsible for the supply and distribution of food supplies, cooks and tablakars. The Matbah-ı Amire Administration, consisting of the principal, assistant principal, chief clerk, harem press clerk, tabernacle clerk, clerks, cellar, baker's head, and two stewards, was responsible for the organization of kitchens and personnel, the distribution of food and meals, and the accounts of kitchen expenses. The provisions warehouse was managed by a separate manager.

In addition, there were porters, boatmen, beards, wood-carrying porters, tinsmiths, and weighbridges who weighed the materials, working in the palace kitchens, in charge of transporting food goods. Matbah-ı Amire and Harem-i Hümayun kitchen stewards organized the distribution of materials from the cellars to the palace kitchens and also oversaw the making of dishes, desserts, sherbet and compotes in the kitchen. The clerks, the grocers and the sour cellars assisted the stewards.

The people responsible for cooking the meals in the kitchen consisted of cooks, journeymen and cook soldiers. In addition, the chefs working in the kitchen were divided into kebab maker, rice maker, pastry maker, fast food maker, compote maker, dessert maker and pastry cook. Those working in the palace bakeries were divided as pastry maker, baker, baker, and baker's janitor. The chefs working in the Sultan's kitchen consisted of the head chef, the second chef, the head of the kebab, the head of the dessert, the head of the pastry shop, the head of the fisherman, the head of the dieter, the chefs and their soldiers.

II. During the reign of Abdülhamit, the fisherman's head was only working in the sultan's kitchen. Sultan II. The presence of a fish kitchen and a chef in charge of fish dishes in the palace since the reign of Mahmut II was a novelty compared to previous centuries. In addition, the fact that the cooks working in the palace kitchens in the 19th century worked in separate furnaces according to their specialties made a difference compared to the classical period palace kitchen organization.

Another innovation was that at the end of the 19th century, an interpreter was employed in the palace kitchens. 4 These translators were probably present from the second half of the 19th century to accompany foreign cooks who worked in the preparation of French-style feasts prepared for foreign dignitaries when they came to visit the Ottoman palace.5

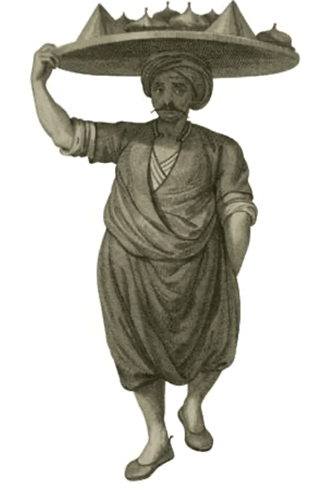

The meals cooked in the palace kitchens were carried to the apartments by the servants called tablakar. The tablakars serving each flat were separate. In 1884-1885, 363 tablakars were working in the palace. Tablakars also carried the food from Yıldız Palace to Dolmabahçe and Feriye Palaces. It is also known that leftover meals are sold by tablakars at affordable prices in the Beşiktaş district. Until 1908, the distribution of food on the tables in the palace continued. II. After the proclamation of the Constitutional Monarchy, the practice of giving food to the palace officials and clerks in the cafeteria began.

The kitchens in the mansions where the dignitaries, dignitaries and state dignitaries lived in Istanbul were in the form of a small model of the palace kitchens. The kitchens were located in a separate place opposite the mansion.

Under the direction of the chief cook, the head of the cellar and the steward, the pastry maker, the aviary, the rice cook, the kebab maker, the vegetable maker, the dishwasher, and the cook worked in the kitchen. Tablakar or ayvaz were responsible for the distribution of food. A small kitchen was also located in the harem. It is known that at the end of the 19th century, as the European-style cuisine gradually became known in the elite circles of Istanbul, as in the Ottoman palace, foreign Frankish chefs also began to work in their rich mansions.

In ordinary Istanbul households, which were mostly located in the garden, the kitchen was located on the floor. In such households, the person responsible for the preparation of the meals was the wife or bride of the house. In the 19th century, as in previous centuries, there were many tradesmen involved in the production and sale of food in Istanbul: milkman, pudding, borek, gullaç, grocery store, vegetable, halvah, pickle, coffee, greengrocer, butcher, tripe soup, fruit seller, candy seller Such as kebab maker, chicken maker, egg maker, trotter, lokma maker, baker, simit maker, boza maker, salep maker, foot coffee maker.

Foodstuffs

We can learn the quality of the foodstuffs used in the kitchens of the Ottoman palace in the 19th century through the matbah-ı amire notebooks, that is, the kitchen accounting books. In these notebooks, the amount of rations given to the kitchens for a month or longer were recorded. According to this information, it is possible to see which foods and which vegetables and fruits are consumed in the palace kitchens according to the seasons, which type of oil is used in the meals, whether red meat or poultry and fish are used most in the preparation of the meals.7 The most important point when purchasing food for the Ottoman palaces attention to the provision of the best kinds of foodstuffs.

Some foodstuffs such as rice, spices and fruit were brought from the provinces and provinces of the empire from long distances for the use of the palace. In addition, Istanbul, as one of the commercial centers of the empire and with the privilege of being the capital, had a rich variety and continuity of food and provided the materials to be used in the Ottoman palace kitchens.

In addition, vegetables and fruits from the gardens of the Ottoman palaces, butter, milk and yogurt from the dairy farms were among the foods given to the palace kitchens. The foodstuffs used in the Ottoman palace kitchens in the 19th century can be classified under the following headings: sheep and lamb meat, poultry and game animals, fish, cereals, milk and dairy products, legumes, fats and oils, sugar and honey, spices, dry and fresh. fruits, vegetables.

In the 19th century, the most preferred and consumed foods in the palace were mutton, rice, flour and butter. In addition to mutton, offal types such as head, trotter, liver, tripe and bumbar were among the materials used in the kitchen. Lamb meat was consumed only during the lamb season, that is, from ruz-ı Hızır to ruz-ı November. And it was more luxurious than mutton.

Veal consumption was almost nonexistent in the Ottoman palace cuisine. Beef, on the other hand, was only used for making pastrami and sausage. It was seen that veal was taken to the palace kitchens since the 1880s for the preparation of European dishes, which will be served to foreign guests as fillet, sirloin, veal thigh and chop.

Chickens and chickens were regularly among the supplies given to the palace kitchens . The American origin turkey (chicken-ı turkey), which entered the Ottoman palace cuisine from the 18th century, was consumed in small quantities in the 19th century. If turkey could be found, it was first supplied to the kitchens of the sultan and the harem. Contrary to previous periods, the consumption of pigeons in the palace was not common in the 19th century.

Since game animals are not included in the kitchen notebooks of the first half of the 19th century, very clear information can not be obtained about the consumption of game meat in the palace. However, towards the end of the century, in the documents dated later, it is seen that poultry such as turkey, chicken and chicken, as well as game meats such as duck, goose and quail, were taken to the kitchens of Yıldız Palace, especially for the kitchen of the sultan.

Palace Culinary CultureOne of the innovations that took place in the Ottoman Palace cuisine in the 19th century compared to previous periods was the consumption of fish. According to the accounting records of the Ottoman palace kitchens, dried fish, caviar, fish roe, eel and cod were among the foods bought for the sultan's kitchen in the documents containing the food materials purchased for the kitchen of Mehmet the Conqueror in 1471.8

However, these lists did not include all the fish species of the Bosphorus. According to the findings of Arif Bilgin, who made an important study by examining the palace kitchen accounting records between 1450 and 1650, fish was never among the foodstuffs taken to the Ottoman palace regularly and in large numbers.

Most of the time, the amount and type were not given in the kitchen notebooks, and only the money paid for the purchase of fish was recorded. According to the documents of this period, there were no fish and seafood in the palace kitchens, except for carp and dried fish, which are freshwater fish. Or the types of fish taken were not known, just as they were until the middle of the 19th century, because they were only recorded as “baha-yi semek”, that is, fish purchase.9

According to the findings of Tülay Artan, who made an important study on the Ottoman palace cuisine culture in the 18th century by making use of the appointment lists, fish was not among the foodstuffs that were constantly sent to the palaces and mansions that were appointed from the kitchens of the Topkapı palace. However, according to the documents, various fish -with the exception of the bonito- were included among the foods found in the palace and mansion cellars without specifying the breed.10

According to the Ottoman palace kitchen accounting records, in the 19th century, more fish, caviar and fish eggs were consumed in the palace than in previous periods. Especially lakerda, caviar, fish roe and kipper were among the delicacies frequently consumed in the palace. Fish roe and Azov caviar were also among the foods offered as iftar in Ramadan.

Until the end of the 19th century, there were records in the palace kitchen notebooks showing that various types of fish (semek-i mutevvia) were bought mostly. There were also records showing that sardines, sturgeon, toric and coral fish were bought for the sultan's cuisine. As we learned from the accounting records of the palace kitchens from the 1870s onwards, more kinds of fish were started to be bought especially for the sultan's kitchen.

Sultan II. In these records belonging to the reign of Abdulhamid, turbot, goldfish, bluefish, mullet, rockfish, sea bass, flounder, red mullet, haddock, mackerel, swallow, coral were among the fish species that entered the sultan's kitchen. Shellfish such as oysters and mussels were not generally consumed in the palace cuisine. However, seafood such as lobster was bought to be used at the banquets to be held for foreign guests.

Wheat was the most consumed grain in the 19th century palace cuisine. The flour obtained from wheat was used in bread making as it is today. It was also the basic ingredient of pastries, which formed an important part of the Ottoman cuisine. Breads differed according to the quality and origin of the flour used. The various types of flour purchased were as follows, depending on where they came from: Dakik-i Asitane (Istanbul flour), dakik-i Beykoz and dakik-i Rus. In addition, the quality of the flour in question was reported with standard phrases such as top quality flour (dakik-i hass), medium quality flour (dakik-i hass medium).

Bread was mostly made in palace bakeries, but it was also bought from commercial establishments. The best type of bread was the one made from the best quality white and pure flour (nan-ı hassü'l-hass). Other bread types mentioned in the documents include the daily bread of the Ottoman individual (nan-ı saint), medium quality hass bread (nan-ı hass medium), mediocre bread (nan-ı adi), flat white bread (fodula), long good white bread. There were bread (frincala), phyllo bread and wholemeal flour loaf. Apart from the flour types we mentioned, he used a special flour for kadayif (dakik-i kadayif). Bulgur was consumed in small quantities in the palace cuisine.

Palace Culinary CultureIn the 19th century, the second type of grain that was as popular as wheat in the Ottoman court was rice (erz). Rice was used primarily in the production of rice (grain), which is the main dish of the palace tables. Rice, especially from Egypt, was taken to the palace. Unlike previous centuries, another grain that was regularly consumed in Ottoman palace kitchens in the 19th century was Viennese barley (barley-yi-beç). Starch and semolina, which are mainly used in dessert making, were also among the materials used in the palace kitchens.

Güllaç, which consists of thin phyllo dough made with starch, was among the supplies given to kitchens regularly, especially in Ramadan, as it is today. Another product made from wheat was vermicelli made in several varieties: Special vermicelli, yellow vermicelli, white vermicelli, Istanbul vermicelli and durum vermicelli. Pasta (macaroni) was an innovation in 19th century Ottoman cuisine. Lentils, chickpeas, broad beans and beans were the types of legumes in the culinary culture of the period. Dried beans originating from America were a new food in the palace kitchen notebooks since the 19th century.

Milk, yogurt and butter were among the basic foods consumed in the Ottoman palace cuisine in the 19th century. As an extension of the Central Asian Turkish culinary tradition, yoghurt consumption was common in Ottoman folk and palace cuisine in the 19th century. Milk, yoghurt and dairy products (Üsküdar and Eyüp butter and yoghurt) were purchased from the Istanbul market. In addition, at the end of the century, there was a dairy farm within the Yıldız Palace.

Here, yogurt, butter and cheese were made with milk obtained from Dutch and Egyptian cows, and these foods were distributed to the sultan, the mother sultan and other palace officials according to their rank. Especially cream obtained from buffalo milk was among the foods consumed in the palace. Brine (white cheese), cheddar, kashkaval, Albanian and tulum cheeses were the types of cheese that were taken into the kitchens. Especially in late documents, it is determined that imported cheeses such as Dutch cheese and Parmesan cheese were taken to the palace kitchens, albeit a little.

In the 19th century Ottoman palace cuisine, as in the previous periods, the main type of oil used in cooking was butter and plain oil (revgan-ı Sade), which was obtained by boiling and salting butter. According to the cookbooks of the period, a small amount of tallow or lard was sometimes used in making clarified butter. Olive oil consumption was very low in Ottoman palace cuisine compared to butter. Other oil types used in the kitchen were kidney oil (revgan-ı çerviş) and lard oil, but to a lesser extent.

Sweet and sugary foods have always been an important part of the

Ottoman palace culinary culture. Sugar and honey were not only used in desserts but also in drinks such as sherbet, compote and some dishes. Sugar was a luxury and expensive ingredient used in making sweets. It was therefore limited to the consumption of the rich. Honey, molasses and dried fruits were sweeteners used in dessert making, especially in public cuisine. In the 19th century Ottoman palace cuisine, large amounts of sugar were used.

There were two types of sugar taken into the palace kitchens and halvah: granulated sugar (sugar-i gubar) and head sugar (sugar-i minar). In the 19th century, salt brought from Wallachia, rock salt and lake salt were used in the Ottoman palace kitchens. Black pepper, cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, gum, cumin, saffron, red pepper, allspice, sumac, turkey walnuts, thyme and vanilla were the types of spices mentioned in kitchen notebooks towards the end of the century. Among these spices, American origin red pepper, vanilla and allspice were an innovation for the 19th century Ottoman palace cuisine. In previous periods, the intake of these spices was not observed. Other flavorings and natural additives used in the kitchen included rose water, orange flower water, lemon juice, verjuice, vinegar, gelatin (fish-i mulberry), confectioner's dye, and scarlet.

Dried and fresh fruits were consumed in abundance in the Ottoman palace cuisine of the 19th century. Almond, pine nut, pine nut, hazelnut, walnut, chestnut and raisin varieties (grape-i murg or grape-i bird, seedless grapes and razaki), dried apricots, prunes, dried figs, dried pears and dried cherries are included in the material lists. the aforementioned dried fruits. In particular, both fresh and dried fruits were used in making compotes and sherbets. A wide variety of fresh fruits were consumed in the palace.

It was recorded in the accounting lists that more than one variety of the same fruit was supplied to the kitchens. Lemon, sweet lemon, orange, citrus, tangerine, citron, apple, Albanian apple, Amasya apple, lime, sweet pomegranate, sour pomegranate, pear, Maple pear, Mustafa bey pear, Bozdogan pear, Inebolu pear, quince, bread quince , Besme quince, Rumeli nut, plum, Serfice plum, glass plum, bag plum, damson, green plum, pineapple, date, Razaki grape, currant, sergeant, seedless grape, black grape, cherry, currant, peach, Cherry, melon, Manisa melon, strawberry, green almond, fresh hazelnut, Damascus apricot, Persian apricot, watermelon, cranberry and fig were among the fruits consumed in Ottoman palace kitchens.

Among these fruits, the orange was a fruit that started to be recognized in the Ottoman palace and Istanbul from the 18th century. Mandarin, on the other hand, entered the Ottoman cuisine at the end of the 19th century. Warm climate fruits such as bananas and pineapples were not included in the royal culinary lists in the 19th century. However, the fact that pineapple is included in Ottoman cookbooks of the late 19th century shows that this fruit is known in the elite Istanbul cuisine.

Like fruits, vegetables were among the foods consumed in large quantities in Ottoman cuisine. Products such as vegetables, salads and fruits were supplied to the palace kitchens both from Istanbul markets and from private gardens such as Feriye, Ortaköy and Aynalıkavak on the shores of the Bosphorus and Golden Horn. In the palace kitchens, eggplant, zucchini, squash, artichoke, cucumber, okra, broad bean, beans, string beans, purslane, green and red pepper, green and red tomatoes are bought in the spring and summer, while cabbage, carrot, celery, spinach, leek are bought towards the end of summer. such as winter vegetables began to be bought.

Other types of vegetables consumed in autumn and winter included radish, cauliflower, turnip, celery, Jerusalem artichoke, pumpkin, and spinach. In addition, it was possible to find summer vegetables such as eggplant, green beans, zucchini and tomatoes in the Ottoman palace kitchens during the winter months. These vegetables were specially brought in limited quantities from the southern provinces of the empire. Dry onions and garlic were taken into the kitchens in large quantities.

Parsley, dill, and fresh mint were the fresh herbs that entered kitchens every season. Vine leaves were consumed fresh and in brine, and at the same time, hazelnut, quince and tomato leaves were given to the kitchen pantry. Wild herbs such as hibiscus, chicory, sorrel and musk were also among the materials used in the palace kitchens. Among the dry vegetable varieties purchased for the palace kitchens, dry okra was the most common. Okra of African origin, which entered the Ottoman palace cuisine from the 17th century, was consumed in abundance in the 19th century, both fresh and dried. Dried okra was brought to the Ottoman palace from Edirne and Amasya.

The 19th century was a period in which new vegetables of American origin such as tomatoes, potatoes, fresh peppers, beans, local mackerel, squash, pumpkin and corn began to be widely used in Ottoman cuisine. According to the palace kitchen notebooks, tomato (kavata), a fruit of American origin, entered the Ottoman palace in the 1690s. It was originally consumed as green. However, it was during the 19th century that the use of red tomatoes in elite Ottoman cuisine became widespread. Even in the 1840s, tomatoes and tomato paste were not yet widely used in Istanbul cuisine.

For example, in the Ottoman cookbook named Melceü't-Tabbahin, which was published in 1844, the dishes in which tomatoes were added consisted of only seven or eight recipes. It seems that tomatoes and tomato paste, which are indispensable ingredients of almost every dish in

Turkish Culinary Culture today, had not yet reached their present position. Known in some parts of the Balkans since the beginning of the 18th century, maize entered the Ottoman palace cuisine in the 19th century. Potato, another vegetable of American origin, was also introduced into the palace kitchens during this period.12

Mushroom, which can be discussed in the vegetables section, is not generally seen among the materials bought in Ottoman kitchens and cellars. Only since the 1870s, pickled mushrooms have been found in the accounting books of the palace kitchens, especially for the matbah-ı hass. Mushrooms, peas, asparagus and artichokes supplied to the kitchens in tin cans show that the Ottoman courtiers were introduced to canned goods imported from Europe at the end of the 19th century.

The foodstuffs used in the Ottoman palace kitchens in the 19th century are largely similar to the cookbooks of the period reflecting the distinguished Istanbul cuisine. According to four Arabic-letter Turkish cookbooks published in Istanbul between 1844 and 1900 and an Ottoman cookbook published in English in London, the recipes using mutton and lamb are much more than those using veal and beef. .13 In the percentage analyzes made according to the ingredients used in the recipes in the 19th century cookbooks, it was seen that the amount of mutton and lamb used in all recipes was 8.6%, while the amount of beef and veal was 1%.

According to the cookbooks, chicken and chicken are the most used materials in poultry. Game birds such as geese, ducks, quails, partridges, pheasants and turkey can be seen in the cookbook Ev Kadını, which was published only in 1882-1883 and contains many recipes made in European style. In all the recipes in the cookbooks, the recipes containing poultry meat are 2%, and the recipes containing game meat are 0.7%. Tripe, trotter, liver and bumbar are also included in cookbooks.

The biggest difference between the materials used in cookbooks and the materials used in the palace kitchen is manifested in the use of fish and seafood. Compared to the limited consumption of fish in the palace, Istanbul's fish richness is seen in recipes found in 19th century cookbooks.

The amount of fish used in the recipes is almost the same as for mutton and lamb. According to the recipes in all the books, the amount of fish used in the recipes is 7.7%. The absence of seafood such as mussels and scallops in the palace kitchen notebooks indicates that these foods were not consumed much in the palace, but seafood such as mussels, scallops, oysters, shrimps and lobsters, which are frequently used in the 19th century cookbooks, show that these foods were used in the Istanbul cuisine of the period. Caviar and fish roe were foods consumed both in the palace and in Istanbul in the 19th century.

Clarified butter and butter are the most commonly used oils in 19th century recipes, as in the palace. Soups, pilafs, pastries, dumplings, stuffed meats, stews and even fried foods were prepared with clarified butter. The use of olive oil, on the other hand, is limited to salads, some types of frying, stewing, dishes prepared with seafood and false stuffing. Sugar and honey are very common ingredients in cookbooks. Because desserts, sherbets, compotes and jams take up a lot of space in cookbooks. Wheat and rice are the most used grains in recipes in cookbooks, with their use in flour, vermicelli, noodles and starch. Bulgur is almost never included in cookbooks reflecting Istanbul cuisine.

Pasta is a new ingredient used in the 19th century Istanbul cuisine as well as in the palace cuisine. Chickpeas, lentils, broad beans, and towards the end of the century, dry beans are among the legumes used in the recipes in the books. In dessert recipes such as milk, rice pudding, pudding, chicken breast; in pastry recipes such as cream, baklava, bread kadayif; Meadow cheese and feta cheese are used in pastry recipes.

The use of spices in 19th century cookbooks is less diverse than the recipes in Şirvani's cookbook14, which reflects the classical period Ottoman cuisine. The use of spices such as saffron, musk, coriander, gum is less. The most preferred spice types in the 19th century were cinnamon and black pepper. Contrary to today's Turkish cuisine, cinnamon was also used in savory dishes in the 19th century. For example, a pinch of cinnamon is sprinkled on mutton, chicken and fish dishes and sweet-sour dishes made with verjuice or lemon juice. Red pepper, allspice and vanilla are spices that started to be used in cookbooks in the 19th century as well as in palace cuisine. Rose water and orange flower water are used to sweeten some desserts, compotes and sherbets.

According to the cookbooks, fresh fruits were used especially in compotes, sherbet, syrups and jams in Istanbul cuisine. In addition to fruits such as sour cherries, apricots, plums, apples, pears, grapes, oranges, pomegranates, citrus, strawberries, grapes, peaches, lemons, quince, and pistachios, the leaves of flowers such as rose, violet, jasmine, poppy are also used in making sherbet and jam. were materials. In stews cooked with prunes, dried apricots, apricots, chestnuts, dried cherries;

in stuffed fresh melon and apple meat; Fruits such as peaches, quince, apples, sour cherries, prunes, dried apricots and dates were used to make desserts. All the vegetables bought in the palace kitchens were in the recipes in the cookbooks of the period. Vegetables were mostly used in dishes cooked with stuffed meat and cubes. Vegetables and fruits were also pickled. Tomatoes, potatoes, beans, corn, fresh peppers, yams were the new vegetables mentioned earlier and were not mentioned in pre-19th century cookbooks.

Meals

Our knowledge of the dishes cooked in the Ottoman palace kitchens in the 19th century cannot be clearly revealed because we do not have recipes that are proven to belong to the palace and the menu of the palace is limited. The menus of the invitations and banquets organized in the Ottoman palace since the end of the 19th century are the sources that can be used about the dishes cooked in the palace. However, since these menus mostly belong to the banquets prepared in honor of foreign guests in the palace, the dishes they include are examples of French cuisine. For this reason, it is not possible to say that it fully reflects the 19th century Ottoman palace cuisine.

It is possible to get an idea about the dishes cooked in the palace according to the food items mentioned in the kitchen accounting books of the palace and the names of the pots, pans and plates taken to the kitchens.

Because the usage areas of pots, plates and containers are noted in these notebooks. For example, in notebooks, assure, kadayif, bite, börek, kebab, fish, pudding and jam plates, soup, tarator, compote, zerde, pickle bowls, sherbet glass, baklava tray, lamb legume, rice pot, halva pot, egg pan, mucver pan purchases are recorded. According to this information, it is understood that the mentioned dishes were cooked in the palace kitchens. In addition, bread kadayif, flat kadayif, wire kadayif, yufka, violet murabbasi, jam candy, bumbar, kebab pita are other foods mentioned in the purchase lists.

Towards the end of the 19th century, it is possible to obtain information about the dishes cooked in the palace through the lists documenting the number of dinner plates and food utensils sent to different apartments in the palace. According to these documents, meals are sent from the kitchens to the apartments in the palace twice a day, in the morning and in the evening. Meals are specified as species in these lists. Soup (soup), rice, börek, meat dish (meat dish), vegetable dish (vegetable food), dessert, compote, fruit under the name of coldness are almost always on the list. Chicken and trotters are sometimes included in the lists.15 Leyla Saz, who spent most of her life in the Çırağan Palace, describes the meals that are sent every day from the kitchen in the palace to the harem apartments in her memoirs.

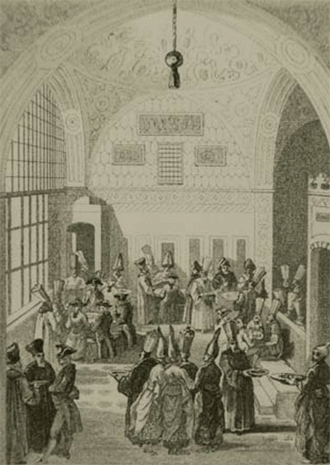

According to Saz, a meal in the palace always consisted of mutton or lamb, sometimes chicken, börek, more than one vegetable dish prepared with diced meat, rice, sometimes pasta and compote made of fresh fruit. Fruits and jams, on the other hand, were always foods in the harem.16 In order to understand the types of dishes cooked in the Ottoman palace in the 19th century, in 1893 II. The menu of a banquet given by Abdülhamit to his students is an important example.

In this feast, which was prepared for a total of 10,321 people, 2888 trays were prepared and 11,552 dishes of food were cooked. The menu consists of stuffed lamb, artichokes with olive oil, semolina halva with milk, fried fish, strawberries, cherries, yogurt, green salad, syrup, lemonade, and ayran.

Palace Culinary CultureMelceü't-Tabbahin (The Cooks' Shelter) published in 1844, A Manual of Turkish Cookery published in London in 1864, The New Cookbook published in 1880-81, Housewife published in 1882-1883 and 1900 The Chef's Head, which was published in 2007, constitutes the sources referenced in this study. Written by Mehmet Kamil, one of the teachers of the Mekteb-i Tıbbiye, and published in 1844, Cooks' Refuge is important in that it is the first cookbook written after the anonymous cookbook19 written in the 18th century.

A Manual of Turkish Cookery published in London by Türabi Efendi, a relative of the Egyptian Khedive, is almost the English translation of Mehmed Kamil's book. It has different features from the other two cookbooks -Yeni Cookbook and Ev KadınıMelceü't-Tabbhin, which were published in the 1880s. Because the new recipes in these books show the European eating habits and innovations that were fashionable in elite circles in Istanbul at the end of the 19th century.

Meals found in 19th century cookbooks include soups, meat (sheep, lamb, veal), chicken and game dishes, fish, seafood, offal, vegetable dishes, egg dishes, rice, pies, dumplings, milk and fruit desserts. They can be grouped under jams, compotes, sherbet and syrups, appetizers and salads.20 In 19th century Istanbul cuisine, soups are prepared with meat or chicken broth; It was sometimes served with cinnamon sprinkled on it, as in fish soup, liver soup, and sour soup. According to the books, mutton, chicken and fish dishes were prepared with four main cooking techniques: kebab, stew, cutlet and frying.

Kebabs were prepared by cooking the meat on a skewer directly over coal fire and the meat in a pot over low heat on the stove or in the oven. Onion juice was the most common ingredient used in the preparation of kebab meat. In fact, cutlet was also a type of kebab. The most important difference was that the meat for cutlet was thin and unnerved, and that lamb, lamb and chicken meats, which were often grilled, were then cooked in very little liquid on the frying pan.

But cutlets prepared with fish were served directly with lemon or tarator without being cooked again. Stews prepared with sheep, lamb, beef, chicken, rabbit and trotter were another cooking technique common in the cuisine of the period. Stew was a cooking technique by slowly boiling pieces of meat in its own boiling water, covered.

Meatballs, which form a separate category among meat dishes, were prepared with mutton or lamb minced with a knife or line, and cooked with the kebab or frying technique or in a little water. Another cooking method mentioned in the books was frying called pans. In general, fries were prepared by dipping fish such as mackerel, anchovy, mussels, sheep or lamb livers in flour and deep frying in hot oil.

In the 19th century Istanbul cuisine, another type of food cooked with the stew technique with little water and olive oil was fish and beef stews served cold. The stews prepared with only vegetables such as tomatoes, dry beans and leeks were included in the cookbooks published after 1880. Prepared with veal, trotters, fish, mussels and oysters, pilaki21 were flavors that reminded Istanbul's Christian community culinary culture. Because pilaki was one of the dishes prepared by the Christian community in Istanbul, especially during fasting periods, such as stuffed stuffed meats and seafood. These dishes were an important part of the elite Istanbul cuisine, which was shared and created by the Muslim, Christian and Jewish communities in the 19th century.

Egg dishes prepared by breaking eggs into chunks after frying an ingredient such as onion, spinach, minced meat and pastrami in clarified butter were another type of food in Istanbul cuisine. The pastries, which are basically prepared by dividing the dough made with flour, salt and water into pieces and then rolling out thin phyllo dough, were very diverse in Istanbul cuisine in the 19th century, as in the past. In addition to the simple pastry doughs prepared with flour, salt, water and sometimes eggs, there were also pastry doughs and leaf doughs made by mixing butter. Börek was made by filling wide phyllo with different materials.

Stuffed with ground beef roasted with onions, feta cheese mixed with parsley and dill, chicken meat, roasted onions, trotters and spinach were used in pastries. Pastries were cooked in different ways: on a low fire in a large tray such as yufka pastry or water pastry, or in the oven, on a sheet like pancake, or by boiling them in hot oil like puff pastry or in water like ravioli and Tatar pastry. Pilaf had an important place in the 19th century elite Ottoman cuisine. Pilafs, which were usually consumed with compote at the end of the meal, were made with rice only. Pilafs were also prepared with mutton and lamb, chicken, fish, mussels and vegetables such as eggplant and tomatoes.

Vegetable dishes were always cooked with cubed mutton or minced meat in a pan with a mixture of clarified butter and water. They were meat and vegetable dishes cooked for a long time in plain oil and little water. Corn, lemon juice, salt, cinnamon, mint, garlic were flavoring ingredients used in vegetable dishes. Shrugging was the name given to vegetable dishes made by frying vegetables such as eggplant first, and then cooking them with pre-cooked meat by shaking them in a pot. In vegetable dishes, tomato puree, juice or paste was not used in early recipes. The ingredients used for flavoring were vermicelli sour and lemon juice. In the cookbook, The Housewife, published in 1882/83, tomato jelly was used in some vegetable dishes.

Moussaka was a method of cooking fried vegetables in oily water by laying layers of minced meat between them. Stuffed vegetables were prepared by stuffing the vegetables with a mixture of minced meat, rice, onions, spices and parsley and cooking them in a saucepan with the addition of clarified butter and water. Stuffed meat, prepared with eggplant, squash and cucumber, was sometimes first dipped in oil and fried and then flavored with sour plum or verjuice juice in a pot and cooked on a straw with little water added. Stuffed meat prepared with hazelnut leaves, quince leaves, and spinach leaves was also called wrap. Stuffed melon and pumpkin stuffed with minced meat cooked with onions, rice, salt, pepper, almonds, peanuts and currants set an example for sweet-salty dishes cooked with meat in the late Ottoman cuisine.

Stuffed stuffed with olive oil were prepared with olive oil, onions, rice, pine nuts, currants, sugar, salt, cinnamon, wrapped in vine leaves or stuffed with vegetables such as eggplant. Stuffed stuffed with olive oil were flavored while cooking with lemon juice, sour plum or cherry. Vegetable recipes cooked with olive oil and eaten cold, which we call olive oil dishes in Turkish cuisine today, are also found in cookbooks that were first published in the 19th century. These dishes were referred to as vegetable dishes, not under a separate title. Another method applied while cooking vegetables was deep frying technique. Eggplant, zucchini or carrots were fried in plenty of olive oil or clarified butter and served with yoghurt or a sauce with vinegar, garlic and honey.

In cookbooks, salads were prepared by themselves with ingredients such as lettuce, cauliflower, tomatoes, cucumbers, green beans, broad bean sprouts, and chervil, and flavored with a simple dressing such as olive oil-lemon or vinegar mixture. Edible flowers such as parsley, fresh mint and dill, and even redbud flowers and rose petals adorned the salads. In Istanbul cuisine, pickles prepared with vegetables and fruits were consumed especially in winter. There are pickle recipes for almost all types of vegetables, some fruits such as melons, watermelons, raw apples and grapes in cookbooks. In addition to these, some fish species were also pickled.

Apart from salads and pickles, tarator prepared with walnuts, hazelnuts or almonds had an important place in 19th century cuisine. Tarator was a kind of paste prepared with bread crumbs and crushed hazelnuts or walnuts, lemon juice, olive oil, salt and garlic. According to cookbooks, this paste was served with grilled fish, lobster, rockfish, mackerel, or with vegetables such as thinly sliced cucumbers, boiled spinach, and green beans. It was called fish roe tarator, which was crushed and mixed with olive oil and lemon juice.

Desserts and beverages prepared with fruit juice have a very important place in the 19th century Istanbul cuisine. In fact, indulging in sweet and sugary foods is a centuries-old tradition in Ottoman cuisine. Desserts, which are the most important tastes offered in celebrations and feasts, also have a ceremonial meaning as a symbol of happiness. It is a tradition to serve sweets such as baklava and kadayif on special occasions such as marriage and circumcision ceremonies. Desserts prepared in the 19th century Istanbul cuisine can basically be grouped into several main groups: sherbet dumplings, halvah, pudding and rice pudding type desserts prepared with milk, ashura, applesauce, fruit desserts, cookies, jams, candies and Turkish delights. In addition to these, compotes, sherbet and syrups prepared with almost all kinds of dried and fresh fruits are among the desserts.

European Tastes

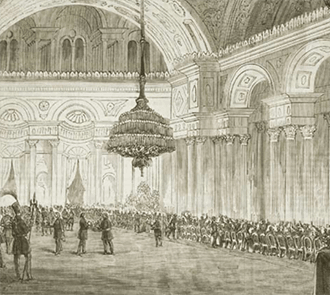

Since the second half of the 19th century, while foreign guests were hosted in the Ottoman palace, European-style banquets began to be organized both in terms of table setting and the food served. The meals in these European-style banquets, which are organized with cutlery, knives and personalized service sets on the table and chair, consist of Turkish and European examples. In some palace kitchen notebooks from 1850, it is mentioned that both Turkish and European dishes were prepared for the banquets prepared for foreign guests. For example, a banquet was held at the Beylerbeyi Palace on May 9 in honor of Prince Napoleon, who visited Istanbul in 1854 due to the Crimean War.

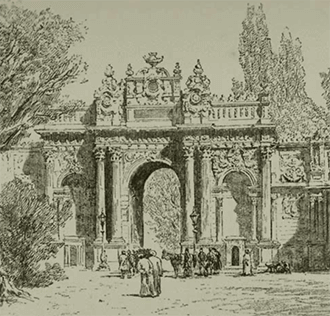

In the document in which the materials taken to the palace kitchen for this invitation were recorded, it was noted that both Turkish and European dishes would be served.22 A good example for the European banquets held in the Ottoman palace is Sultan II. It is a feast held in Dolmabahçe Palace for Ottoman pashas and high-ranking foreign soldiers and ambassadors in honor of the completion of the construction of Dolmabahçe Palace in 1856 during the reign of Abdülmecit and the victory of the Crimean War.

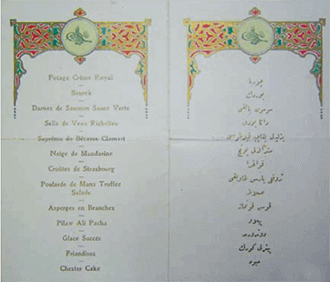

Both Turkish and European dishes were served at this feast. The menu of the banquet includes traditional Ottoman dishes such as börek, pilaf, kadayif and baklava, as well as outstanding French cuisine such as potage Sévigné, paupiette à la reine, croustade de foie gras à la Lucullus. In other palace menus from the end of the century, there are examples of banquets prepared in European style in honor of foreign guests. The meals served at these banquets are indicated by the Turkish and French menus.

Until the last days of the Ottoman palace, while hosting important foreign guests, banquets reflecting the synthesis of French and Ottoman cuisine continued. According to the palace menus of the early 20th century, the majority of the dishes served at these banquets are examples of French cuisine, with the exception of rice and pastry.

Various consomes, small pastries called bouchée served as hot hors d'oeuvres, fish with champagne sauce and caviar sauce, game meat with truffles and foie gras, game meat with jelly, beef fillet served with garnish, asparagus with cream, hollandaise sauce, cakes and tarts are at these feasts. These are examples of foreign dishes served.23 Since the second half of the 19th century, while foreign guests were hosted in the Ottoman palace and its surroundings, French cuisine was preferred, which can be explained by the fact that elite French cuisine dominated the gastronomy world in Europe at that time.

In the 19th century, French cuisine was at the top of the culinary hierarchy in Europe. French cuisine began to be adopted as a fashion in European palaces and elite circles. This development also affected the Ottoman palace. The Ottoman rulers did not stay away from the French cuisine, which their rivals and allies adopted as a sign of exclusivity, and preferred to host them in their own gastronomic language.

In this way, they both underlined their own distinctiveness and showed that they could speak the same language as their rivals or allies. Another reason why foreign guests were hosted in the palace was the change in the memorandum and the offering of a European-style kitchen, as some elements of European culture began to be recognized and adopted by the Ottoman elite, especially the palace, in parallel with the reforms implemented by the Ottoman administrators from the Tanzimat period.

The French cuisine, which began to be recognized primarily through official banquets in the Ottoman palace and its surroundings, over time, led to the acceptance of new dishes and the formation of new taste patterns in the elite Istanbul cuisine. Restaurants, cafes and patisseries reflecting the European style opened around Pera and Galata in Istanbul since 1850 also played an effective role in the recognition of new dishes.

European dishes, which mostly bear the characteristics of French cuisine, started to be recognized in elite Istanbul circles from the second half of the century. In Melceü't-Tabbahin, which was published in 1844, there were only two dishes of foreign origin under the names İstofato Kum Makaronya, İstofato kum-potato stew, while the number of new dishes in the New Cookbook and Housewife, published after 1880 it should be more.

In these cookbooks of the late 19th century, European dishes, new soups such as vegetable soup, Hungarian soup, pea soup, oyster soup, goat soup, tomato paste, broths, meat and chicken broths, pates, pastas, roast beef, breaded cutlets are some meat dishes such as steak, ragu, and garnishes and preserves. Recipes called egg paste, olive oil paste, lobster paste, mussel paste, oyster and scallop paste, spicy paste, tomato paste are actually various sauce recipes.

Mushrooms, tomatoes, potatoes, iced onions, bread, spinach, sorrel, peas, asparagus, chicory and French peas are examples of side dishes mentioned in the books. Pates, a type of paste made from game meats, poultry and fish, are dishes that have entered the Istanbul cuisine from the French cuisine, such as garnishes. Creams, cakes, biscuits and ice cream bars are the new style European dessert types featured in the New Cookbook and Housewife.

Vanilla pastry, savarin, almond pastry, European pastry, tart pastry types; Biscuits with pineapple, chestnut, spoon, rice, lemon and orange, cream, pistachio, sugar, hazelnut and chocolate are examples of biscuits, that is, crispy varieties. Bitter almond cream, common cream, solid cream, lemon, vanilla cream, pudinka or pudding are examples of creams.

Since the second half of the 19th century, the European style cuisine, which was used when foreign guests were hosted in the Ottoman palace, influenced the elite cuisine of Istanbul over time. Some examples of French dishes prepared for foreign guests were added to the Ottoman cuisine and entered the cookbooks as European dishes, and some of them led to the formation of new dishes with Turkish and European characteristics over time. One of the best examples of this synthesis cuisine, which is formed by the combination of Turkish and European cooking techniques, is the sultan's liked meal.

Tas kebab, which was served only with roasted eggplant paste at first, changed over time and became integrated with French bechamel sauce and grated cheese and assumed a completely hybrid and at the same time delicious personality. Seeing that there are more recipes from French cuisine in Turkish cookbooks with Arabic letters published since 1920 shows that European cuisine continued to be fashionable in the elite Istanbul cuisine in this period. Some recipes are included in these books with both Turkish and French names.24

In the last period of the empire, the distinguished Istanbul cuisine exhibits a rich food culture that has been going on for centuries and includes new taste patterns. Meals that symbolize two different taste cultures, such as baklava and pie, kebab and roast beef, eggplant shakes and iced onion garnish, rice and pasta, chicken breast and cream, tarhana and oyster soup, pate and tarator, are side by side in Istanbul cuisine in the late 19th century. is located. New food ingredients of American origin such as tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, beans, allspice and vanilla are on the tables together with flavors such as yoghurt, yufka, pastrami, ravioli, and tutaç, whose origins are based on the far Central Asian nomadic Turkish cuisine.

Unlike previous centuries, the distinguished Ottoman cuisine in the 19th century differed from the classical Ottoman cuisine by interpreting fish and seafood with cooking techniques such as cutlet, rice or kebab, which it knew before, as in the examples of bluefish cutlet and scallop pilaf. Another striking change in the 19th century Ottoman cuisine compared to the 15th and 16th centuries is the gradual separation of sweet, salty and sour flavors in dishes and the simplification of the spices used in the dishes. The recipes of the 19th century do not have sweet-salty flavor patterns and spice variations in which a lot of fruit and meat are combined as in the 15th century.

In the 19th century, as in the previous periods, Ottoman palace kitchens had the feature of being the central kitchen where fine examples of Ottoman cuisine were presented with its detailed kitchen structure, personnel organization and superior quality of materials. While the 19th century Istanbul cuisine was formed as a reflection of the Ottoman cuisine, which had developed over the centuries in the center of the palace, it was nourished by the above-mentioned innovations and created a synthesis culture by blending the dietary habits of different communities that already existed in its own structure.

Source;

This study is mainly based on “19. 21st Century Istanbul Food Culture: Nutrition, Cuisine and Table Manners based on doctoral dissertation work.

2 Prime Ministry Ottoman Archives. BOA, DBSM, no.11700 (1247-1248/ 1831-1833)

3 Esemenli, Deniz. Ottoman Palace and Dolmabahçe, Homer Bookstore, Istanbul, 2002, p. 124, 216-217.

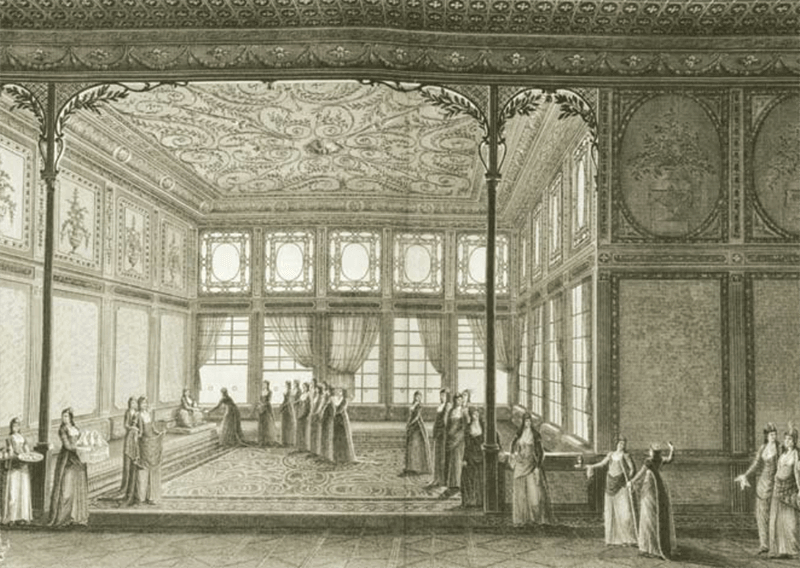

tablakar

(Mouradgea d'Ohsson, Tableau général de L'Empire Othoman, II, Paris 1790; Coşkun Yılmaz Archive).

4 BOAs. Y.PRK. HH., no. 12/13 (1300/ 1884-1885)

5 Samanci, Ozge. Ottoman Feasts in the French Style: A Study on the Gastronomic Language of Fourteen Feast Menus Between 1914-1918.” Food and Culture, Istanbul: Çiya Publications, no. 8, p. 48-62, 2007.

6 Lütfi Simavi (Magazine Lütfi Bey), The Last Days of the Ottoman Palace, Hürriyet Publications, pp.42-43.

7 Samanci, Ozge. “19. Ottoman Palace Cuisine in the 19th Century” Food and Culture, number 4, Istanbul: Çiya Publications, 2006, p. 37-59. “19. Eating and Drinking Habits of the Ottoman Elite in the First Half of the 20th Century” Our Table Nur, Our House Mamur (pleasure). Suraiya Faroqhi. Christoph Neumann, Istanbul: Publishing House, 2006, p. 185-209.

8 Barkan, Omer Lutfi. Documentation, vol. IX, no. 13, Ankara: TTK, 1979, p. 238-240.

9 Bilgin, Arif. Ottoman Palace Cuisine, Istanbul: Bookstore, 2004, pp.196-197

10 Artan, Tülay. “Aspects of the Ottoman Elite's Food Consumption: Looking for “Staples”, “Luxuries” and “Delicacies” in a Changing Century” in Consumption Studies and the History of the Otoman Empire 1550-1922, / ed. Donald Quataert, New York: State University of New York Press, 2000, p. 142

11 Samanci, Ozge. “Sultan II. Fish at Abdülhamit's Table” Food and Culture, issue 11, Istanbul: Çiya Yayınları, pp.150-154.

See 20 on food. Samanci, Ozge. Croxford, Sharon. 19th Century Istanbul Cuisine Accompanied by Original Recipes, Istanbul: Medyatik, 2006, p. 19.26.

21 Pilaki is a word of Greek origin. (see) Eren, Hasan. Etymological Dictionary of Turkish Language, Ankara: 1999., p. 333.

22 BOA. Cevdet Saray, no. 3335.

23 Samanci, Ozge. “Ottoman Feasts in the French Style: A Study on the Gastronomic Language of Fourteen Feast Menus Between 1914-1918”. Food and Culture, Istanbul: Çiya Publications, no. 8, p. 48-62, 2007.

24 Ahmet Şevket, Cook School, İstanbul, Sühulet Library, volume I, II. 1336 (1920), Head Chef Tosun, Woman Cooking at Home or The Perfect Cookbook, Istanbul, Amedi Printing House, (first edition 1921) 1927.

As Has Chef Ahmet Özdemir, I see the source:

Assoc. Dr. I sincerely thank Ms. Özge Samancı for her academic studies titled "Istanbul and Ottoman Palace Culinary Culture in the Last Period of the Empire" and wish her success in her professional life. It will definitely be considered as an example by those who need it in professional kitchens and the gastronomy and culinary community.