For example, in her work called Şehr-i Sefâ: Istanbul in the 18th century, in which she examines the urban spaces and cultural transformations in 18th century Istanbul, Shirine Hamadeh says that we can read the spatial transformations that took place in this period through poetry...

Ottoman Garden Culture and Poetry Assemblies in the 16th Century

Rümeysa ŞİŞMAN

There is an atmosphere dominated by stereotypes and general judgments about the Ottoman cultural world. Recent research opens the door to approaches that will allow us to make evaluations away from clichés. And these studies reveal how urban spaces and cultural life interacted and influenced each other in Ottoman society.

For example, in her work called Şehr-i Sefâ: Istanbul in the 18th century, in which she examines the urban spaces and cultural transformations in 18th century Istanbul, Shirine Hamadeh says that we can read the spatial transformations that took place in this period through poetry. He emphasizes that these transformations, which are the result of newly emerging social classes, are visible in all literature in general and poetry in particular.2

It is possible to observe the structure of the urban spaces of 18th century Istanbul not only through poetry, but also through the places where poets gathered and communicated with each other. In fact, poetry and the memorandum shaped around it give clues to a general understanding of the cultural structure and social life of Ottoman society. These views, which Hamadeh put forward for the 18th century, can also be said to a certain extent for the 16th century.

At this point, of course, it is necessary to consider how the Ottoman cultural world was structured. According to Bahar Deniz Calis, the cultural structure of the Ottoman society is based on a cosmological hierarchy.

Calis is of the opinion that Ottoman social life was established in harmony with Ibn Arabi's cosmological hierarchy. This hierarchy was also reflected in the rituals in intellectual activities, and all the practices and arrangements in the society expressed this cosmological structure. “The cosmological hierarchy was very important because it placed all aspects of society in a religious order, encompassing all spiritual, ideological, social, cultural and individual domains.”3

In his doctoral thesis, which he prepared based on this general determination, Calis examines the relationship between the ideal garden image, which is an important element of

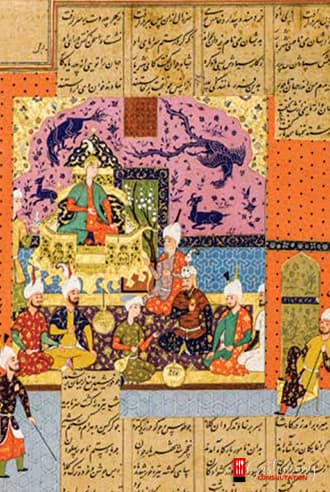

Ottoman culture and literature, and the real garden practices of this culture. As a result of his examinations on miniatures and various texts, he makes the following determination: Members of an assembly or those who participate in a certain assembly sit in circles around the food. The host who organizes the assembly has the most privileged position.

Such assemblies are usually set up by rivers or ornate springs. In this cosmological structure, the inner spaces are always superior to the outer ones. And gardens are also interior spaces compared to general public life.4

In the 16th century, the meeting places of the palace elite and poets consisted of private houses, taverns, shops, lodges and palace or private gardens. Among these gathering places, gardens had a special importance. The Sultan and his palace were at the center of intellectual life. These distinguished people gathered in the sultan's gardens (private gardens) or private gardens to read poetry and have fun.

Safavid garden, (Mullah Mosque', Heft Evrang, Metropolitan Museum)

There is an atmosphere dominated by stereotypes and general judgments about the Ottoman cultural world. Recent research opens the door to approaches that will allow us to make evaluations away from clichés. And these studies reveal how urban spaces and cultural life interacted and influenced each other in Ottoman society.

For example, Shirine Hamadeh examines the urban spaces and cultural transformations in 18th century Istanbul, Şehr-i Sefâ:

In his work called Istanbul in the 18th century, he says that we can read the spatial transformations that took place in this period through poetry. He emphasizes that these transformations, which are the result of newly emerging social classes, are visible in all literature in general and poetry in particular.2

It is possible to observe the structure of the urban spaces of 18th century Istanbul, not only through poetry, but also through the places where poets gather and communicate with each other. In fact, poetry and the teşrîfat shaped around it give clues to a general understanding of the cultural structure and social life of the Ottoman society. These views, which Hamadeh put forward for the 18th century, can also be said to a certain extent for the 16th century.

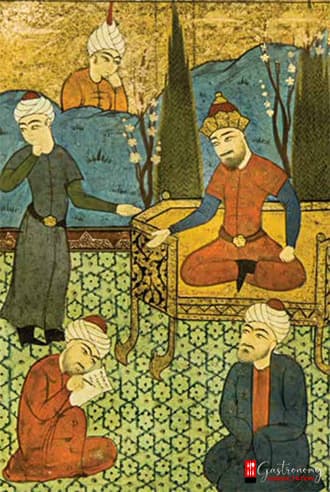

At this point, of course, it is necessary to consider how the Ottoman cultural world was structured. According to Bahar Deniz Calis, the cultural structure of the Ottoman society is based on a cosmological hierarchy. Calis is a poet reciting his poetry in the presence of Ibn Arabi's cosmological hierarchy of Ottoman social life - the Sultan (Anonymous, Tezkiretü'l-Şuara, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek)

In A Garden for the Sultan: Gardens and Flowers in the Ottoman Culture, Nurhan Atasoy lists the characteristics of the Ottoman gardens as follows: “It is surrounded by high, fence-like walls; trees were planted by the walls; although there are many different types of trees, at least a few cypress trees and preferably spring blooming trees; rectangular flower beds placed at tree roots; a garden pavilion; a lectern and chair or, if there is a pool or spring water in front of it, a seat for the sultan to sit; the stables of wild animals and horses bred for recreational riding as a symbol of the sultan's rule over three continents.”5

As the palace was the center of cultural and intellectual life, the courtesies of the sultans were also important in terms of being included in the palace life. For this reason, creating works in the literary and visual arts was almost the key to entering cultural life. Also, because these arts were costly, a patronage system was necessary. Therefore, regarding the main actors of the assemblies in the gardens, it should be emphasized that the patronage of the palace had a central place in Ottoman divan poetry and the emergence of a class of poets for the first half of the sixteenth century.6

Besides the cultural and intellectual life, being able to write poetry or understand literature also served as a qualification test for choosing the person to be placed in government offices. For example, a person who produced a poem or other work also aimed to attract the attention of the authorities for an appointment or promotion.7

Here we see how politics, economics and art were intertwined in Ottoman culture and the deep connection between them. Taking this link into consideration, Walter Andrews concludes that poetry and society in Ottoman culture mutually constitute each other. 8

In the Ottoman culture, the patronage culture of the Timurids and the Chagatai literature were considered the most ideal targets. For this reason, art had a vital importance in the centralization of the system. During the Ottomans' efforts to systematize and centralize the administrative structure, art always played an important role, expressing the dominance of the center over social life.9

Where did people gather in Ottoman society?

Public gathering places is one of the intriguing questions. It is possible to answer this question for the aforementioned centuries: People used to come together in shops, bozahanes, barber shops and baths in their neighborhoods. These meetings were also held in the city or in the gardens around it, but in these assemblies there were mostly members of certain social groups, either members of the palace or members of the guild, that is, people consisting of elites or scholars.

However, there was no strict membership rule applied to enter these gardens, where anyone was not allowed to participate. Some natural groupings determined the membership structure, because guilds had different meeting places. Only those who were appointed by a certain authority (that is, those who were appointed by a certain authority) could attend the assemblies and meetings held in these private gardens.

In Harmony with the Natural

The importance of gardens in Ottoman social life can also be traced through the garden culture that appears in divan poetry. All acts of lovers and loved ones in Divan poetry mostly occur in such garden assemblies. There are many different names given to the assemblies in the gardens in Ottoman literature: bezm, 'ıyş, chat, assembly, rev. These assemblies usually begin after sunset or at night and last until the sun rises.

In 16th century Ottoman Istanbul, there were no fixed and sharp rules that determined the garden culture. The Ottoman gardens of that period can be seen as the basis of many cultural encounters.

Not only the gardens decorated by the Muslims, but also the Byzantine gardens have an effect on the gardens of Istanbul. Timurid-Iranian culture is another cultural color that was active in sixteenth-century Istanbul. However, Ottoman gardens differ from other gardens with these features, as they aim to reflect the gardens of paradise and therefore they take care to preserve the natural state of the garden as much as possible. The structure of the gardens is like a manifestation of the idea of being in harmony with the natural.

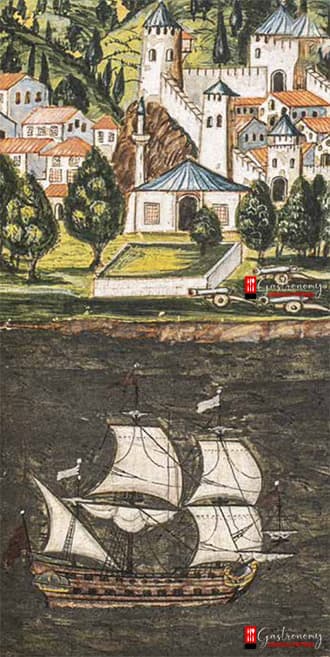

In some gardens, there was also a small pavilion for the sultan or small buildings built to spend time or shade. Gardens located on the sea coast were more preferred, as they facilitated transportation. There were many gardens belonging to sultans and dynasty families in Istanbul. The palace gardens were located along the Bosphorus. According to Necipoğlu, “16. 19th-century travelers confirm that the shores of the Bosphorus, especially on the Asian side, are full of large summer palace gardens.”11

The records of these gardens were kept in great detail. The gardens that belonged to the Sultan were not only places of entertainment and excursions; At the same time, it was the responsibility of these gardens to provide the vegetable, fruit and flower needs of the palace. Those who operated these gardens were working under the command of the chief gardener of the palace. The palace bought the products of these gardens in proportion to its needs, and the remaining products were the income of the owner of the garden.12

The gardens of the palace dignitaries were hardly visible. In addition to the dynasty, the notables of this palace could also convene an assembly in their gardens. However, due to the death of the owner of the garden or his exile to another place, or due to the sultan's edict, these gardens were later generally joined to the palace gardens. This is the reason why these gardens are so rare and rare in the records.

Gülru Necipoğlu “16. Since no Ottoman gardens from the 19th century have survived, a study of them must be limited to texts and pictures.”13 In other words, we only have miniatures and literary texts as sources to understand the garden culture of the time.

Tezkires Shedding Light on Cultural History

Tezkires come first among the written sources about the Ottoman Istanbul of the 16th century. Tezkires include detailed information about cultural life as well as giving place to biographies of poets. For example, while describing the life of poets, information can be obtained about the different professional equipment of poets, the daily life of people, and the characteristics of entertainment and travel venues. The poets' life, birth and death dates and places, their works, meeting places with other poets, information about both their daily lives and official relations are included in these biographies.

In the 16th century biographies, Zâtî's book shop, Çağşircı Şeyhî's shop, the house of the son of the Woodmaker İskender Ahmed Çelebi, Atmeydanı, Tahtakale, Efe Tavern in Galata and the private gardens of Topkapı Palace or Üsküdar are the most important gathering places of the period. stands out as. But these gardens are also important as they are the gathering places of the Ottoman elite.

As a genre in Ottoman literature, poet biographies also reveal how important poetry was in Ottoman society. Sehî Bey, Latifî Çelebî, Âşık Çelebî, Kınalızâde Hasan Çelebî, Ahdî and Beyânî can be counted as the most important biographies of the sixteenth century. Although the biographies written by these individuals give information about the relations and communication networks between the poets, they do not use very obvious expressions about the meeting places.

In fact, studies carried out to date show that private gardens, with the exception of palace gardens, were not included in the records.14 Therefore, Âşık Çelebi's Tezkire is of special importance in terms of giving detailed information about the gardens where the poets gathered. In Âşık Çelebî's biographies, the gardens of the palace elite such as Efşancı Mehmet Garden, Kara Bâlîzâde Garden, Yunus Pasha Garden, Janissary Iski Garden and Sirkeci Bahşî Garden are mentioned. As Âşık Çelebî's main purpose was to record the lives of poets who lived in that period, he mentions these gardens only as meeting and entertainment places for poets.

For example, Efşancı Bahçesi is first mentioned under the subtitle of Vasf-ı Efşancı, that is, the characteristics of Efşancı.15 Efşancı Mehemmed Çelebî is introduced as a very talented person. Sultan II. Efşancı, who lived towards the end of Mehmet's reign, had mastered handwriting and fast writing. He was also known for his mastery of the 'solid' art. By cutting colorful papers, he created gardens that compete with reality in beauty with the art of ka'ti. Due to his mastery in his art, he was invited to the palace many times, and during these visits, many gifts and gifts were given to him. Efsancı is also known as the first person to perform the 'solid' art.

Ottoman Garden Culture and Poetry Assemblies in the 16th Century

Chapter in the presence of the Sultan (Anonymous, Majlis-i Shuara, Metropolitan Museum)

After enumerating those who followed him in this art, Âşık Çelebi describes Efşancı's art in detail. One of Efşancı's works is in the Topkapı Palace Museum, and Nurhan Atasoy includes this work in his book A Garden for the Sultan and describes it in detail. on the other hand, it shows an asymmetrical feature. It is accepted that this work in the museum is a depiction of Efşancı's real garden. The plants, trees and flowers in the real garden that Efşancı established after he fell ill and had to give up his 'hard' art are described in detail in Âşık Çelebi's biographies.

By the way, it should be pointed out that the flower culture has a very old history in Istanbul. The interest in flowers naturally led to an increase in the number of shops selling flowers, and this number also shows how intense the flower culture and dealing with flowers was throughout the Ottoman history.17

Efşancı's garden was one of the gathering places of scholars, poets, bureaucrats and ruling elites. Especially the grand vizier İbrahim Pasha and the Sultan used to visit this garden frequently. Near his death, Efşancı had a school built in the garden and bequeathed to be buried next to this school. Another garden was opened by Kara Bâlizâde when Efşancı was managing the garden, and Âşık Çelebi mentions this synchronicity and emphasizes the superiority of Efşancı's garden.

Competition of poets in the presence of the sultan (Mîr Seyyid Ali, Hamzanâme, British Museum)

Another garden owner mentioned in Âşık Çelebî's biographies is Kara Bâlîzâde.18 Contrary to the other gardens he mentions, Kara Bâlizâde's garden is recorded as a private garden. Day and night entertainments and assemblies are organized in its garden and guests are hosted.

Kara Bâlizâde garden is the only garden built in the Persian style çeharbağ (four gardens) style in the 16th century and is located around Kabataş on the European side of the Bosphorus. As Necipoğlu stated, Salomon Schweigger in his travel book especially II. He mentions that this garden was of great importance due to its proximity to the Topkapı Palace during the reign of Selim.20 One of the distinguishing features of the Black Bâlizâde garden is its structure and shape. According to Âşık Çelebî, another feature of this garden is that the rules of the assemblies are flexible.

Assemblies held both indoors and in gardens had a set of rules that the participants had to abide by. A participant should have an attitude and condition that is appropriate to the attitudes and behaviors of the garden owner and the guests who come there. Despite such rules, everyone was given the opportunity to participate in Black Balizade's garden as they wished. But there were still some special rules. For example, Kara Balizade did not allow those who came to his garden to be pessimistic, joyless and hopeless; Everything that would cause sadness should be left outside the garden.

Another garden mentioned by Âşık Çelebî belonged to Işki-yi Sâlis (Third Work). His hometown is Yenihisar, one of the settlements close to Istanbul, and his real name is İlyas and he is a janissary. According to Ahdi, one of the 16th century tezkire writers, İşkî's father was also a janissary and the reason why İşkî was sent to retirement was not because he was thought to be dead, but because of illness.22 After that, İşki was engaged in civil service and earned many mansip thanks to the poems he wrote.

Later, he establishes a garden by the sea in Üsküdar. The garden, full of flowers, birds and trees, becomes a gathering place for many different groups, starting with distinguished people. The guests who come to the garden read poems, play games, listen to music, play chess. However, after a short time, Iski returns to Yenihisar and dies there. Unlike the owners of other gardens, Âşık Çelebi also mentions that İşki is also a poet. As a matter of fact, sixteenth century biographies such as Kınalızâde, Ahdî, Beyânî and Latifî included the life and poems of İşkî in their works.

Another garden owner, Sirkeci Bahşî, has a garden in Beşiktaş.23 Bahşî, who is mentioned as a friend of the poet Gazali (Deli Brother), is from Bursa. While he was a student at the Sahn Madrasa, an earthquake occurred while he was drunk, and he decided not to drink again. When he stops drinking, he becomes addicted to pickles. For this reason, he allocates part of his garden to the cultivation of pickled vegetables and partly to the production and sale of vinegar. The fruits and vegetables of Bahşî's garden, where scholars and prominent people gather on holidays, are very famous. Another feature of the garden is that illiterate and uneducated people are not accepted to the assemblies there.

Many examples that can be found while reading the 16th century biographies have features that give a portrait of the social and cultural life of the period. Because the places where poets gathered and communicated were an important part of the 16th century urban space structure. But unlike the 18th century gardens and gathering places, we do not have the opportunity to monitor the visibility and continuity of the 16th century gardens. The lack of such continuity, that is, the disappearance of these gardens, may also have an effect on public spaces such as coffee houses, which were just beginning to emerge in the city at that time. But this issue needs to be examined separately. By simply pointing out this issue, let us reiterate that we can only trace the 16th century gardens through literary texts and miniatures. That's why 16.

****

1) Istanbul Şehir University Cultural Studies Program Graduate Student Turkish Lecturer 2) Hamadeh, Shirine. 2010. City of Sefa: Istanbul in the 18th Century. Istanbul: Communication Publications. 3) Calis, Bahar Deniz. 2004. Ideal and Real Spaces of Ottoman Imagination: Continuity and Change in Ottoman Rituals Of Poetry (Istanbul, 1453-1730). PhD diss., Middle East Technical University. p.10. 4) Age, p. 11. 5) Atasoy, Nurhan. 2002. A Garden for the Sultan:

Gardens and Flowers in Ottoman Culture. Koç Culture, Arts and Communications Inc. and Aygaz A.Ş. s. 53. 6) Kim, Sooyong. 2005. Minding the Shop: Zati and the Making of Ottoman Poetry in the First Half of the Sixteenth Century. PhD diss., The University of Chicago. s. 13. 7) Ibid, p. 34. 8) Andrews, Walter. 1985. Poetry's Voice, Society's Song, Ottoman Lyric Poetry. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. s. 143174. 9) Kim, p. 15. 10) Necipoğlu, Gulru. 1997. The Suburban Landscape of Sixteenth-Century Istanbul as a Mirror of Classical Ottoman Garden Culture in Gardens in the Time of the Great Muslim Empires: Theory and Design. Attilio Petruccioli (eds). Leiden; New York: EJ Brill. s. 32.11) Ibid., p. 33. 12) Artan, Tülay. 1993.

Istanbul Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Era from Past to Present. Istanbul: Turkish Economic and Social History Foundation. vol.1 p.543 13) Necipoğlu, p. 32. 14) Erdogan, Muzaffer. 1958. Istanbul Gardens in the Ottoman Era. Foundations Journal. Ankara. IV: 149-182. And Zeki, Mehmed. 1335 [1917]. Vineyards and Recreations Literature in Istanbul in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Istanbul, II 30: 76-78. 15) Âşık Çelebi, 979/1572. Meşairü'ş-şuara: review text. Prepared by Filiz Kilic. Istanbul : Istanbul Research Institute, 2010. vol.2. p.998 16) Atasoy, p.73. 17) Sakaoglu, Necdet. Istanbul Encyclopedia of Floristry from Past to Present. Istanbul: Turkish Economic and Social History Foundation. vol.2 pp.508 -512. 18) Âşık Çelebi, p.1204. 19) Atasoy, p. 275; Erdogan, p. 170, 20) Necipoğlu, p. 32-34. 21) in love

A ship in the Bosphorus (Anonymous, Topkapi Treasure Archive)

Celebi, p. 1090. 22) Baghdad Covenant. 2009. Gülşenü'ş-Şuara. Prepared by Süleyman Solmaz. Ministry of Culture Publications.s. 229. http://ekitap.kulturturizm. gov.tr/belge/1-83501/ahdi---gulsen-i-suara.html 23) Âşık Çelebî, p. 1642.

REFERENCES

1) Andrews, Walter. 1985. Poetry's Voice, Society's Song, Ottoman Lyric Poetry. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. 2) Aşık Çelebi, 979/1572.

Meşairü'ş-şuara: review text. Prepared by Filiz Kilic. Istanbul : Istanbul Research Institute, 2010. 3) Atasoy, Nurhan. 2002. A Garden for the Sultan: Gardens and Flowers in Ottoman Culture. Koç Culture, Arts and Communications Inc. and Aygaz A.Ş. 4) The Baghdad Covenant. 2009. Gülşenü'ş-Şuara.

Prepared by Süleyman Solmaz. Ministry of Culture Publications. p.229. http://ekitap.kulturturizm.gov.tr/belge/1-83501/ahdi---gulsen-isuara.html 5) Calis, Bahar Deniz. 2004. Ideal and Real Spaces of Ottoman Imagination: Continuity and Change in Ottoman Rituals Of Poetry (Istanbul, 1453-1730). PhD diss., Middle East Technical University. 6) Istanbul Encyclopedia from Past to Present. Istanbul: Turkish Economic and Social History Foundation. 7)

Erdogan, Muzaffer. 1958. Istanbul Gardens in the Ottoman Era. Foundations Journal. Ankara. IV: 149-182. 8) Hamadeh, Shirin. 2010. City of Sefa: Istanbul in the 18th Century. Istanbul: Communication Publications. 9) Kim, Sooyong. 2005. Minding the Shop: Zati and the Making of Ottoman Poetry in the First Half of the Sixteenth Century. PhD diss., The University of Chicago. 10) Necipoglu, Gulru. 1997.

The Suburban Landscape of Sixteenth-Century Istanbul as a Mirror of Classical Ottoman Garden Culture in Gardens in the Time of the Great Muslim Empires: Theory and Design. Attilio Petruccioli (eds). Leiden; New York: EJ Brill. pp. 32-71. 11) Zeki, Mehmed. 1335 [1917]. Vineyards and Recreations Literature in Istanbul in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries. Istanbul, II 30: 76-78. 12) Zeki, Mehmed. 1335 [1917]. Old Istanbul Vineyards. Edebiyât-ı Umûmiyye Magazine. Istanbul, II 32: 107-109.